Disclaimer: The views and opinions expressed by the author(s) do not represent the official position of Barbados TODAY.

by Adrian Sobers

“Slaves who read, Frederick learned from him, are slaves who run away.” – (The Color Of Abolition)

One of the most striking sentences (so far) in Linda Hirshman’s The Color of Abolition, came in the chapter Frederick Douglass’s History in Slavery, “If ever an act could be attributed to divine providence it was the moment when the slave met the alphabet.” Douglass was better off than the poor white children in his neighbourhood in one regard; he always had bread at home.

“This bread I used to bestow upon the hungry little urchins, who, in return, would give me that more valuable bread of knowledge.”

Hirshman adds, “Douglass knew their bread [knowledge] was worth more than his [literal loaves].” We should not commit the same error as the Marxists who, as Sir Roger Scruton observed, “regard ideas as by-products of economic forces” and “dismiss the intellectual life as entirely subservient to material causes.”

The alphabet, and the modern day spear of the mind,

are our best allies.

Words like “genius” and “brilliant” are thrown around so much these days that they have become all but meaningless. Stephen Budiansky put it well in his review of The Man from the Future, “Indiscriminately applied these days to everything from Elon Musk to tips for cooking chicken in your dishwasher, the word “genius” has arguably lost whatever meaning it might have had.” (Besides,

as a personal philosopher friend posted, intelligence

is not a virtue.)

Readers obviously have different levels of intellect, interests, along with varying personal and professional commitments. You know yourself and situation best and can tackle the list in whole, in part (or not at all).

It also depends how deep you want to go into the topic (and your pockets). Legal scholar James Boyle observed, “You have never heard true condescension until you have heard academics pronounce the word ‘populariser.’”

The list, organised into sections and obviously not exhaustive, would no doubt draw the ire of sophisticated scholars. Good.

It is for the streets; for the average consumer desirous of inoculating their mind from the false narratives, proferred by some of the said sophisticates, concerning

our quantitative quagmire. With that brief introduction out of the way, we can finally move onto the list.

Central Banking/Former Central Bankers: The End of Alchemy; Unelected Power; Keeping At It; The Man Who Knew; Bagehot: The Life and Times of the Greatest Victorian; Radical Uncertainty. Paul Tucker’s Unelected Power deserves special mention here. Our quantitative quagmire is grounded, not in greed, but as Mr. Tucker shows, a gaping governance gap (that still needs closing).

“The most important constraint is that elected politicians should not be able, in effect, to delegate fiscal policy to the central bank simply because they cannot agree or act themselves. The more central banks can do, the less the elected fiscal authority will be incentivized to do, creating a tension with our deepest political values.”

Or, as John Mackay (1914) put it in the foreword of Fiat Money Inflation in France, “Every fetter that could hinder the will or thwart the wisdom of democracy had been shattered.” Western democratic despotism tends to be cloaked in lofty rhetoric and is more subtle than tanks in Tiananmen (but then again there is Mr. Trudeau’s treatment of the truckers).

History and Trade-Offs (Not “Solutions”).

A History of the Federal Reserve, Volume 1 (and Volume 2, Book 2); Boom and Bust Banking. Allan Meltzer’s magisterial magnum opus is a must. Incredible.

You will quickly realise why a reviewer suggested all journalists should read all three volumes. Pay special attention to chapters 6–8 in Volume 2, Book 2.

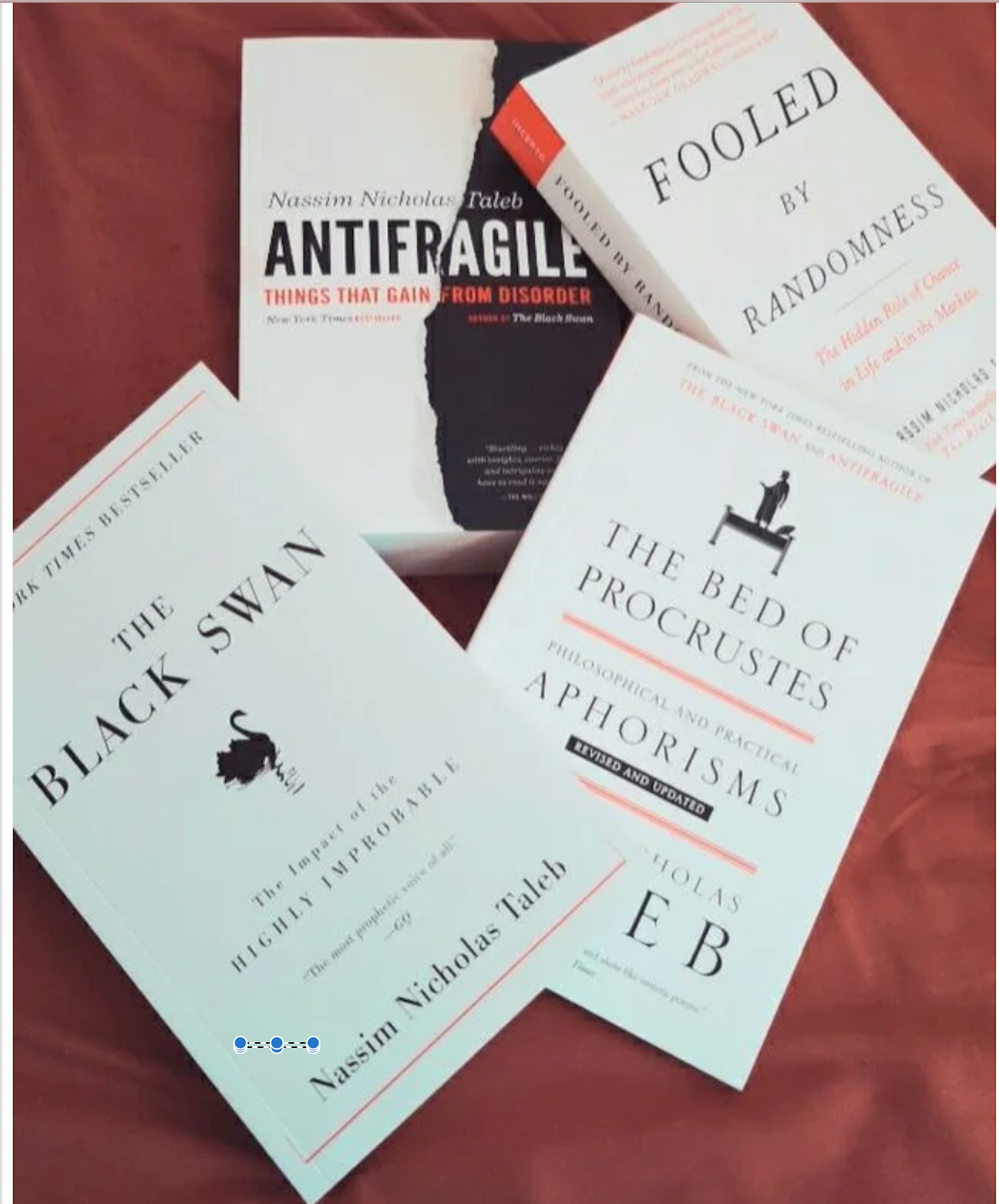

What’s Wrong with Economics? Nothing personal here, purely philosophical. We are dealing with ideas not individuals (even if principals are mentioned). There are good reasons why I keep returning to Nassim Taleb’s Incerto. Antifragile and Fooled by Randomness are

the most helpful in this context but I would highly recommend the entire series. Radical Uncertainty would also be at home here.

I omitted the section on important persons but I will say this much about John Maynard Keynes. Keynes the probabilist, no problems. Keynes the economist, plenty. As for the high priest of central banking Walter Bagehot, he would say to the current crop of central bankers concerning our monetary mess, “This people honors me with their lips, but their hearts are far from me.” Also helpful is Robert Skidelsky’s title that doubles as the name for this section.

Which brings us to the lone title in the final section that grounds everything: Theological.

In Divine Currency, Devin Singh suggests that money and economy cannot be grasped apart from sovereignty and law. This is most evident in Matthew 22:17–22, and the familiar Dominical utterance, “Give therefore to the emperor

the things that are the emperor’s, and to God the things

that are God’s.”

Even if the content of our slogans are true (God will provide), they should not obscure other important lessons. For Singh, the idea of God as central planner and Christ as currency in God’s economy removes the wedge between theology and the world’s “monetary economic realm”. Jerome’s oft-quoted statement about Obadiah is true, it is as difficult as it is short, but this much is clear: God is sovereign and plays an active role in international affairs.

As we limp from one lost decade to the next, far more important than whose image is on an increasingly worthless fiat currency, or whether currency goes digital, is this: whose image is on you? (If God’s, then render accordingly.)

There is no shortage of reasons why the world is coming apart at the seams. One we can mention briefly is that we are still thinking/training using production-line industrial era methods in and for an information age. Another title is more a fitting description of what is needed:

The Great Upheaval. Not in any radical or destructive sense, and certainly not only in education of the

higher variety.

God knows we need it in the economic realm and will act accordingly. Until then, occupy yourself with a title or two. Most importantly, be your brother’s keeper.

Adrian Sobers is a prolific letter writer and commentator on social issues.