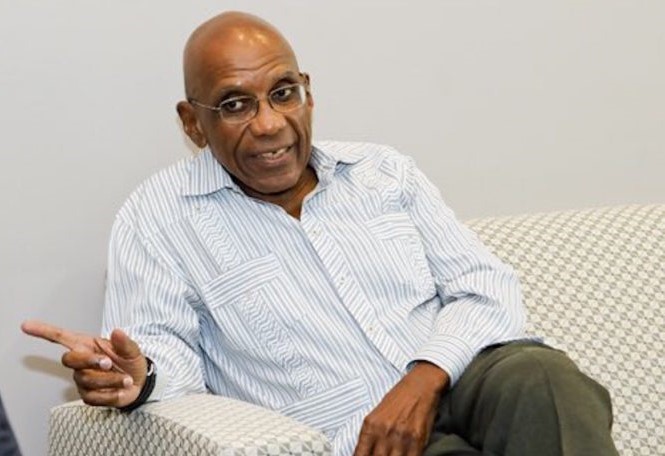

As trade unions and employers’ representatives battle over the pros and cons of importing foreign labour to fill jobs here, former Central Bank governor Dr DeLisle Worrell has declared that there is no need to protect the local job market.

He has also recommended that small countries like Barbados export their best and brightest as a preferred employment strategy.

The noted economist, a former consultant for the International Monetary Fund (IMF) the World Bank and the Inter-American Development Bank (IADB), in his January 2024 economic newsletter on the topic The Migration of Skilled Workers is Essential for the Development of Any Small Economy, said: “Caribbean governments, and the governments of small countries everywhere, should re-think educational policies which are nationalist in orientation.”

“Education should be designed to equip students to be productive internationally; there is no need to protect the local job market. Local graduates must be able to hold their own against all comers. The fact of the matter is that a small economy cannot, by virtue of the limited range of activity in which it can attain internationally significant production, provide employment opportunities for the majority of its most talented population.”

Dr Worrell said if the government wishes to afford each member of the population opportunities to realise their fullest potential, “the official strategy must contemplate the emigration of a majority of their foremost minds and abilities”.

Singling out Jamaica – the second largest economy in CARICOM, with a GDP of $15 billion – Dr Worrell contended that even in the tourist enterprises in which that country specialises, the number of senior managerial, professional and technical jobs on offer is limited, far less than the number of talented young people who enter those occupations each year.

According to Dr Worrell, there is no work at home for those who aspire to jobs in aviation, automobile design, bioengineering and high finance.

“There are no hometown heroes in the scientific, technical, engineering and mathematical fields, and no local mentors for a majority of those with these skills, because Caribbean countries boast few industries that employ such persons,” he said.

“Their models for employment are overseas, as are the job opportunities for those who are trained in these areas. Caribbean educational policies must be tailored in light of this reality.”

Dr Worrell, who headed the Central Bank from 2009 to 2017, and is currently an independent international economic consultant, contended that there is a widely-recognised deficit in tertiary education in science, technology, engineering and mathematics in the Caribbean.

“The challenge is not to supply graduates to work in the region but to raise the quality of Caribbean knowledge and education in these fields, which on the whole is not up to the highest international standards,” he said. “Our governments owe it to our finest minds to give them the best start possible in scientific disciplines, even if there is no possibility of employment for them in the region.”

He said the programme which best demonstrates the potential of science, technology, engineering, and mathematics (STEM) education of Caribbean students is an initiative of the US-based Caribbean Science Foundation, through which more than a hundred regional students have been put on paths for careers at the frontiers of scientific endeavour in North America.

The economist called for a “revision of educational policies which aim to tailor skills to employment requirements in the local economy”.

“The Caribbean’s tertiary level institutions produce large numbers of graduates in managerial, business, professional and personal services, far too many for the requirements of the local economy. Many seek jobs abroad, and many more find local jobs in which they cannot use the skills they have acquired; all too often those jobs are in the public services,” he said.

“Education of the population to the best internationally accepted standards should be the objective of all Caribbean educational systems so that everyone has the choice of a career at home or abroad. Those with an inkling to make their career locally will do so if they can find jobs that pay well and offer good career prospects. Such jobs will most often be with companies that offer internationally competitive tourist, business and financial services, and other efficient and productive enterprises.”

He insisted that other graduates, especially from tertiary institutions, should be supported if they choose to seek jobs abroad.

“Why should Caribbean countries educate students to work abroad when domestic unemployment remains high by international comparison? The reason is that it is impossible to match educational outputs to the jobs on offer locally in an efficient way,” he pointed out.

Dr Worrell highlighted the mismatch between the limited demand for low-skilled jobs and the large numbers in the labour force with limited or no skill.

“The solution for this problem is to improve the quality of primary and secondary education, so as to equip the overwhelming majority of students with the capacity to acquire a level of skill which makes them internationally mobile,” the economic consultant said.

“In this way, the pool of unskilled unemployed dries up, and instead, there emerges a shortage of low-skilled workers for construction, agriculture and similar work. That shortage may be filled by immigrants.”

emmanueljoseph@barbadostoday.bb