I have written and spoken publicly on this subject several times, but I don’t apologise for raising it yet again because I believe it to be an essential step forward in our continued cultural development as a nation.

I have written and spoken publicly on this subject several times, but I don’t apologise for raising it yet again because I believe it to be an essential step forward in our continued cultural development as a nation.

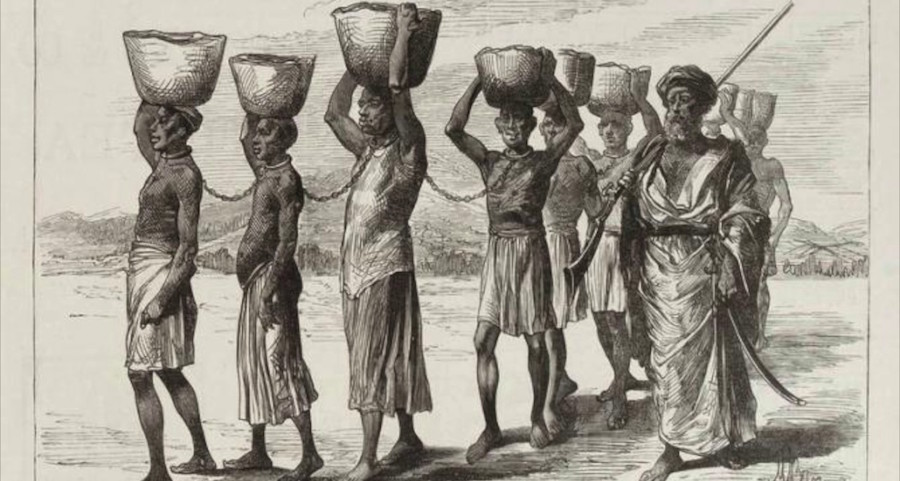

Let me say upfront that what I have in mind is not a modest museum; I’m talking about creating the premier museum of the transatlantic slave trade and enslavement of our African ancestors in the Americas. That doesn’t mean we can’t start small and grow. But let’s think big, please.

Like many others, I use the word ‘enslaved’ rather than ‘slaves’ to describe our ancestors’ position in society. It’s a small but important means of portraying them as human beings, not the property they were treated as at that time.

So let’s look at possible objections to such a project. First, several people I’ve spoken to see no need for such a museum. They argue that the Barbados Museum already has dedicated enough space to slavery in Barbados. My response: while the Museum must be complimented for cataloguing features of enslavement and for sponsoring numerous events highlighting this aspect of our history, a museum dedicated solely to enslavement would be of far greater scope and scale. The period of enslavement, from the mid-17th to the mid-19th century, profoundly shaped the Barbados we live in today.

Moreover, while consistent efforts have been made to preserve as many manifestations of our British heritage, most manifestations of our African heritage have, over the centuries, been unrecorded, deliberately suppressed, or allowed to vanish. Moreover, very few, if any, plantation houses on show today fully highlight the contribution of enslaved labourers and craftsmen to their building and to the success of the plantation enterprise. In the past two or three decades, laudable efforts have been made both by the Barbados Museum and the National Trust to redress this situation. Even so, we need a comprehensive memorial to our enslaved African ancestors that both chronicles their sufferings and celebrates their achievements.

Which brings me to the second objection that is raised: money. You have any idea how much this would cost?

Not really. Probably about B$50 million.

‘Wait!’ I hear, ‘where we going get that from? Oh Lord, the poor Bajan taxpayer.’

The Bajan taxpayers should not have to contribute one red cent. Unless they want to. There’s a large pool of international philanthropic money, including our diasporas in North America and Europe, waiting to be tapped. There are also online fundraising apps that allow you to identify and tap appropriate sources. In addition, there are foreign governments and global foundations that would contribute to such a museum.

Moreover, this is an ideal project for reparations funding from academic and other institutions in the UK and elsewhere. Besides, there are many Barbadians and several philanthropists who live among us who would happily contribute to such a fundamental heritage project provided there’s a sound business plan identifying the scope and phases of the project, including its financial sustainability, and built-in transparency and accountability.

The third objection I hear, and this is an important one, is: but will it be financially sustainable? Or will its operation become a burden on the taxpayer? It will have to be financially structured to be sustainable. Revenue might come from a variety of sources: entrance fees; commercial activities like shops, restaurants, facility rentals, and so on; individual, family and corporate memberships; corporate contributions; endowment income; grants, donations, and partnerships.

A museum of the transatlantic slave trade and enslavement would be a major cultural tourism attraction with wide international appeal and marketability. Besides, part of the capital to be raised for the establishment of the museum should cover operating costs for the first three to five years. All this means, that, whatever happens, it should not be government run. There should be an independent not-for-profit entity under government oversight with accountable management running the museum.

Then, I’m often asked, where are we going to site this museum? I don’t know. There are several possibilities: somewhere within Historic Bridgetown and its Garrison; or land adjoining the enslaved burial ground at Newton; or lands owned by the Codrington Trust adjoining the college in St John, or at and around a disused sugar factory.

Another objection I hear: would not such a museum be a constant reminder of the historical injustices inflicted on blacks by whites and thus stir up racial animosity and destroy social harmony? Shouldn’t we put all this slavery business behind us and move forward into the future? This is an important objection, not because it’s valid — it isn’t — but because it strikes at the root of our problem. We cannot go forward until we go back. What social harmony there is between black and white rests on a precarious footing, for there is a black/white animosity that still continues to percolate just beneath the surface of our society, as is illustrated every time there is an apparent racial incident that causes it to come to the surface and explode. Yet, we seem to want to sweep all that under the carpet. In fact, most of us, both black and white, would seemingly settle for a largely peaceful but deeply suspicious tolerance of the other.

The fact is that all Bajans, wherever their ancestors came from, are profoundly influenced by the cultural heritage of our enslaved African ancestors: the way we speak, play, make music, dance, eat and drink, laugh, love and express our spirituality. And perhaps the most important legacy, our thirst for social justice and our courage in facing and overcoming adversity. Our African heritage is the patrimony of all Barbadians.

It is not that Britain did not have an important influence on our lives, for we live in a creolized society in which our African and European heritages have intermingled to produce a distinct Barbadian/Caribbean cultural identity. Every aspect of our lives is a product of creolization, cricket and carnival are the foremost examples. Nevertheless, the British influence was far less profound than the African. In fact, contrary to the social destabilising argument, a museum of African enslavement, properly conceived and presented, would be a huge impetus to healing, reconciliation, and national unity.

What would be the scope of such a museum? In terms of process, it should encompass the most up-to-date exhibition technology. This, after all, would be both a cultural data bank of materials of the past as well as a theatre of history’s reconstruction. Objects must be enclosed in narratives accompanied by video, audio and interactive technology. And surely, there should be audio guides in at least six languages, including Chinese.

Our artists and architects should be asked to create structures, paintings, murals, sculptures and so on, along with video presentations bearing witness to the Transatlantic Slave Trade, slavery, and the colonial structures of exploitation in which they were embedded.

In addition, the museum must have a strong educational function both in terms of schools and the public, and it must be networked to other similar communities across the world.

In terms of objectives, it should be multi-purposed. One, it should be primarily a memorial to a human tragedy of horrific proportions akin to the Jewish Holocaust, depicting the sufferings inflicted on our ancestors, at the same time as it seeks to bring about recognition, understanding and reconciliation in order to transcend this historic human tragedy. It therefore, should incorporate a sacred place of quiet contemplation.

Two, it should celebrate the resistance, resilience, and creativity shown by our enslaved ancestors under the harshest of conditions, starting with the brutal dislocation of the Middle Passage and ending in enslavement as ‘things’, from which only their bodies, their souls and their collective fragmented memories constituted their resurrection – a testament to the indomitable human spirit. We must never see our enslaved ancestors as passive victims but as forgers of their own destiny; people who used their own imagination, determination, communal bonding, and entrepreneurial skills not only to survive but also to constantly innovate and, ultimately, to triumph.

Three, the museum should illustrate the rich West African civilisational heritage from which our ancestors came. I’m not talking about Egypt, but about the several sub-Saharan empires and kingdoms in West Africa — e.g. Ghana, Mali and Songhai.

Four, the museum should illustrate the historical evolution of such essentialist concepts as ‘tribe’ and ‘race’ — now totally discredited as a biological category — along with other ambiguous concepts like ‘ethnicity’, leading to an exploration of the whole question of creolization, nationality and cultural identity.

Five, the museum should document and illustrate both the lingering negative legacies of slavery, as well as the rich and pervasive African heritage in Barbados that our enslaved ancestors bequeathed to all of us, and which is the root and collective unconscious of our creolized Caribbean identity and of our Caribbean civilisation in which we all rejoice.

(Dr Peter Laurie is a retired permanent secretary and head of the Foreign Service who once served as Barbados’ Ambassador to the United States)