One of the striking features of Barbados’ famous public monument known

variously as the Bussa Statue and as the Emancipation Statue, is the

following very powerful and moving inscription at the base of the

monument:

“Let my children

rise

in the path

of the morning

up and go forth

on the road

of the morning

run through the fields

in the sun

of the morning,

see the rainbow

of Heaven:

God’s curved

mourning

calling.”

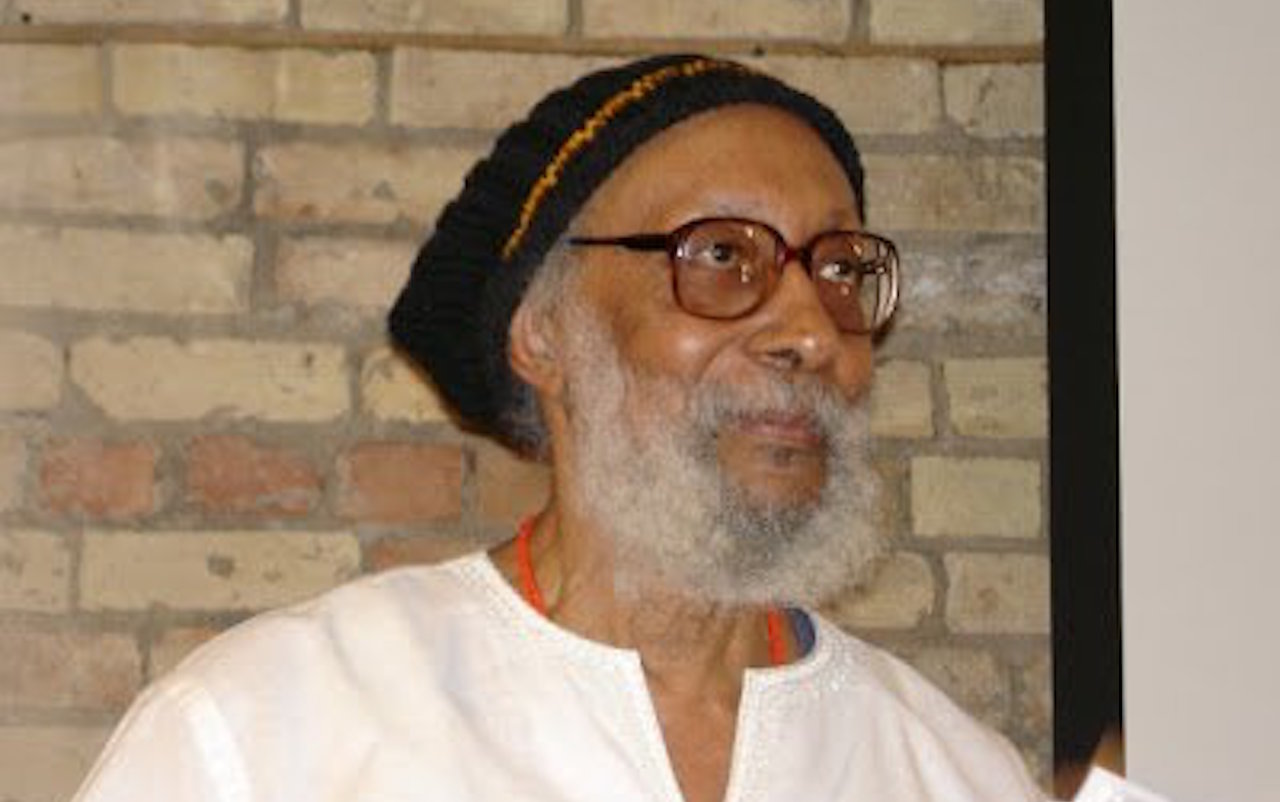

This powerful piece of verse is the creation of Barbados’ most outstanding poet,

historian and culture scholar — Kamau Brathwaite — and

is taken from the poem entitled Tom and published

in Brathwaite’s universally acclaimed poetry collection known as The Arrivants.

It is entirely fitting that Kamau Brathwaite’s work should be

inscribed on the one piece of Barbadian public art that is dedicated

to the quest of the African-Barbadian for liberation, for Kamau

Brathwaite is perhaps the most outstanding example of a Barbadian who

has transcended the spiritual and psychological limitations and

constraints of Barbados’ colonial heritage.

In Kamau Brathwaite, we Barbadians possess the living example of an

extremely creative and intellectually gifted son of the soil who has

taken it upon himself to make that necessary inward journey towards

the core of his being as a child of Africa transplanted in the New

World and shaped by the powerful dialectical (or “tidelectical”)

cultural currents of “Plantation America”.

And because of the magnitude and integrity of Kamau’s effort, Barbados

has received the inestimable gift of a profound native philosopher and

creative artist whose work has helped to clarify many of the critical

cultural and other existential challenges that we face as a nation.

But who exactly is this Kamau Brathwaite — this quiet warrior — who

lives among us at his modest Cow Pastor, Christ Church home, and whose

shepherd-like spirit still watches over our nation? Let us spend some

time looking more closely at the intimate details of the life of this

great Barbadian.

Kamau was born in Barbados in the year 1930 into what was known in

those days as a “coloured middle-class oriented family”, and was

actually christened “Edward Brathwaite” by his parents, Edward and

Beryl Brathwaite. (The African name of Kamau — which means Quiet

Warrior — was bestowed upon him much later in life by the famous

Kenyan writer, Ngugi wa Thiong’o and other African soulmates during a

sojourn in Kenya.)

As a child, young Edward Brathwaite grew up between Mile and a Quarter

in St. Peter and Bay Street (Brown’s Beach) in St. Michael, and

attended such well known primary schools as St. Mathias, St. Mary’s

and Bay Street Primary.

His secondary schooling began at Combermere, where he spent two years

before his parents secured a transfer to Harrison College. And this is

how Kamau has described his stint at Harrison College:

“I went to a secondary school originally founded for children of the

plantocracy, colonial civil servants and white professionals; but by

the time I got there, the social revolution of the 30s was in full

swing, and I was able to make friends with boys of stubbornly

non-middle class origin.

“I was fortunate, also, with my teachers… they were (with two or

three exceptions) happily inefficient as teachers, and none of them

seemed to have a stake or interest in our society. We were literally

left alone. We picked up what we could or what we wanted from each

other and from the few books prescribed like Holy Scripture. With the

help of my parents, I applied to do Modern Studies (History and

English) in the sixth form… and succeeded to everyone’s

surprise in winning one of the Island Scholarships that traditionally

took the ex-planters’ sons ‘home’ to Oxbridge or London.”

So these are the bare facts of Kamau’s upbringing in colonial-era

Barbados. Some 20 years later, Kamau explained the deeper

significance of this upbringing in a very important essay entitled

“Timehri”:

“… my education and background, though nominally ‘middle class’,

is, on examination, not of this nature at all. I had spent most of my

boyhood on the beach and in the sea with ‘beach-boys’, or in the

country, at my grandfather’s with country boys and girls. I was

therefore not in a position to make any serious intellectual

investment in West Indian middle class values. But since I was not

then consciously aware of any other West Indian alternative (though, in

fact, I had been living that alternative), I found and felt myself

‘rootless’ on arrival in England, and like so many other West Indians

of the time, more than ready to accept and absorb the culture of the

Mother Country. I was, in other words, a potential Afro-Saxon.”

But fortunately for Kamau (and for our society), two things saved this

great son of the soil from degeneration into a colonial-minded

“Afro-Saxon”. One was the appearance, in 1953, of George Lamming’s

seminal Barbadian novel – In The Castle of my Skin – with its

exploration of the unique nuances of the culture, sociology and

landscapes of Barbados, and its vindication of our Barbadianism and

West Indianism.

The other was that upon graduating from Cambridge University in 1955

with a degree in History, the young historian and educator secured a

job as an Education Officer in the West African colony of the Gold

Coast (now the independent nation of Ghana). For Kamau, this was very

much a type of spiritual homecoming – a notion that he expressed in

his poem entitled The New Ships as follows:

“Takoradi was hot.

Green struggled through red

as we landed.

Laterite lanes drifted off

into dust

into silence.

Mammies crowded with cloths,

flowered and laughed;

white teeth

smooth voices like pebbles

moved by the sea of their language.

Akwaaba they smiled

meaning welcome

akwaaba they called

aye kooo

well have you walked

have you journeyed

welcome

you who have come

back a stranger

after three hundred years

welcome”

Kamau spent eight years in Ghana, during which time he not only got to

know the country and its people intimately through his work as an

educator, but with the help of his Guyana born wife – Doris Welcome

aka Zea Mexican – he also developed a Children’s Theatre which

produced several of the African-themed plays that he authored in

Ghana.

This was a time of important inward spiritual growth for the Barbadian

historian/educator/playwright/poet – an experience that he explained

in Timehri as follows:

“Slowly, slowly, ever so slowly; obscurely, slowly but surely, during

the eight years I lived there, I was coming to an awareness and

understanding of community, of cultural wholeness, of the place of the

individual within the tribe, in society. Slowly, slowly, ever so

slowly, I came to a sense of identification of myself with these

people, my living diviners. I came to connect my history with theirs,

the bridge of my mind now linking Atlantic and ancestor, homeland and

heartland”.

Simply put, Kamau had discovered his intrinsic “African-ness” – not an

“African-ness” that made him identical with the new brothers and

sisters that he discovered in Ghana, but rather, an “African-ness”

that had been shaped by the dislocation of the Middle Passage and the

centuries of experiences in Plantation America. But perhaps I should

let Kamau speak for himself:

“When I turned to leave, I was no longer a lonely individual talent:

there was something wider, more subtle – the self without ego –

without arrogance. And I came home to find that I had not really left.

That it was still Africa. Africa in the Caribbean. The middle passage

had now guessed its end. The connection between my lived, but unheeded

non-middle class boyhood, and its Great Tradition on the eastern

(African) mainland had been made”.

In 1962 Brathwaite came home not only to a University of the West

Indies teaching job, but also to find himself face to face with the

West Indian Independence Movement that saw Jamaica and Trinidad and

Tobago securing their independence in 1962, to be followed by Guyana

and Barbados in 1966.

It was in this milieu, and with this new understanding of himself,

that Kamau Brathwaite produced some of the most outstanding poetry of

the 20th and 21st centuries! A partial listing of his most important

volumes of poetry is as follows:

Rights of Passage (1967); Masks (1968); Islands (1969);

The Arrivants (1973); Mother Poem (1977);

Sun Poem (1982); X-Self (1987); The Zea Mexican Diary (1993); Dream

Stories (1994); Barabajan Poems (1994); Trench Town Rock (1999);

Ancestors (2001); Magical Realism (2002); and

Born To Slow Horses (2005).

What distinguishes Kamau Brathwaite’s body of work is that he

consciously sought to use and valorise quintessential aspects of our

Barbadian/Caribbean/Afro-American/Pan-African culture. Thus, the

rhythmic structure of his poetry ranges from Jazz to Calypso, Limbo,

Rasta drumming, and to the rhythms and intonations of the Spiritual

Baptists and the practitioners of the West African derived Orisha and

Vodun religions.

Kamau also used his poetry as a vehicle to search for our “Nam” or

inner essence as a people – an exploration that caused him to lift up

and explore our “Nation Language” (commonly condescendingly referred

to as “dialect”), and to pierce beneath the surface of our Caribbean

landscapes and culturescapes to discern ancestors, African orishas,

and fecund and original creation myths and cultural insights.

This body of work is far too voluminous and profound to deal with in

greater detail within the confines of this short essay, but there is

one special poem that I would like to focus on and bring forcefully to my

readers’ attention. To my mind, this poem is the quintessential poem

of the Caribbean independence era! It is entitled Negus and was

first published way back in 1969, in the early years of Independence.

It was relevant then, and it is perhaps even more relevant today! It

is a poem that every single Caribbean citizen should know by heart!

Let us therefore conclude this essay with an excerpt from “Negus”:

“It

it

it

it is not

it is not

it is not

it is not enough

it is not enough to be free

of the red white and blue

of the drag, of the dragon

it is not

it is not

it is not enough

it is not enough to be free

of the whips, principalities and powers

where is your kingdom of the Word?

it is not

it is not

it is not enough

it is not enough to be free

of malarial fevers, fear of the hurricane,

fear of invasions, crops’ drought, fire’s

blisters upon the cane

It is not

it is not

it is not enough

to be able to fly to Miami,

structure skyscrapers, excavate the moon-scaped

seashore sands to build hotels, casinos, sepulchres

It is not

it is not

it is not enough

it is not enough to be free

to bulldoze god’s squatters from their tunes, from their relics

from their tombs of drums

It is not enough

to pray to Barclays bankers on the telephone

to Jesus Christ by short wave radio

to the United States marines by rattling your hip

bones

I

must be given words to shape my name

to the syllables of trees

I

must be given words to refashion futures

like a healer’s hand

I

must be given words so that the bees

in my blood’s buzzing brain of memory

will make flowers, will make flocks of birds,

will make sky, will make heaven,

the heaven open to the thunder-stone and the volcano and the un-folding land

It is not

it is not

it is not enough

to be pause, to be hole

to be void, to be silent

to be semicolon, to be semicolony;”

DAVID COMISSIONG